Submitted by Livia Harriman on Thu, 25/09/2025 - 13:48

Lab-made organoids that mimic reproductive tissues could point to treatments for common conditions such as pre-eclampsia and endometriosis.

In 2017, Ashley Moffett, a reproductive immunologist, walked to the pharmacy near her laboratory at the University of Cambridge in the UK to buy a pregnancy test. But it wasn’t for Moffett. Her postdoc, Margherita Turco, had created what she thought might be the first cluster of cells capable of mimicking the tissue of the placenta — a placental organoid. But she needed a way to be sure.

“We must do a pregnancy test on them,” Moffett said.

If Turco were correct, the miniature ball of cells she had created would secrete HCG, the hormone that triggers a positive pregnancy test. “I took the stick, put it in, and it was positive,” says Turco, now a reproductive biologist at the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland. “It was the best celebration.”

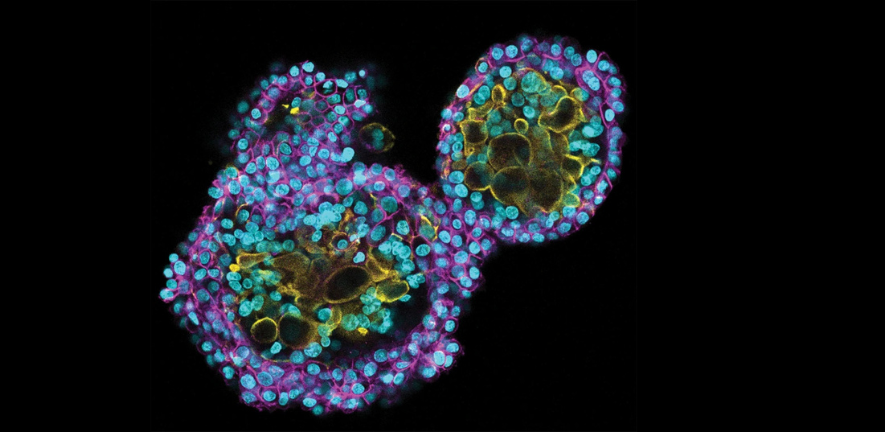

Scientists create organoids like this by coaxing stem cells to grow in a jelly-like substance and self-assemble into clumps of tissue. The typically hollow or solid balls of cells don’t look anything like real organs. But they do take on key aspects of the organ that they’re meant to represent — liver, brain, lung or stomach, for instance.

The mini-organs have the advantage of being more realistic than a 2D cell culture — the conventional in vitro workhorses — because they behave more like tissue. The cells divide, differentiate, communicate, respond to their environment, and, just like in a real organ, die. And, because they contain human cells, they can be more representative than many animal models. “Animals are good models in the generalities, but they start to fall in the particulars,” says Linda Griffith, a biological engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

Over the past decade, organoid research has exploded. Researchers have used them to study early brain development, test cancer therapies and much more. And these 3D models stand to become even more crucial as US agencies, including the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency, aim to move away from animal testing.

Continue reading the article, featured in Nature here: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-03029-0